I went back to delivering two talks this year. I’m not posting my open mic transcript this year because I made fun of a shady company with a thin-skinned founder. Not that one this time: a law of nature mandates that emotionally underdeveloped founders and shonky companies always come in pairs.

I’m not foolhardy enough to make my words that evening a matter of permanent record. Everything I riffed around is self-evidently true; anybody who’s been making audio toys for long enough, including me, has had at least one of their products cloned by them. But it’s a convention of our society that even a meretricious legal letter must be taken seriously. Being a solo engineer, I prefer, to use Rory Sutherland’s formulation, solving problems to winning arguments. Shallow pockets can be an advantage: it’s only worth suing the wealthy. Nevertheless, there are fights I don’t need to pick.

That said, I really did get some stickers made.

Stick them over somebody else’s swag to add a secondary level of sarcasm. Or clone them yourself for a tertiary level. Either way, second-class post is cheaper than defending a defamation lawsuit and pleasingly deniable. If you want some, let me know.

☙ ❧

My main talk this year was about taking over the Mantis synth from Chris Huggett. The product is out, people seem to like it, and it’s getting better bug fix by bug fix. (And what a lot of bugs creep into a project of that complexity: I’m grateful for testers even if the process can be maddening.) The video of that talk will officially be online at some point halfway through next year. The most immediately representative parts of my experience were, of course, the ones I chose to talk about. What I have here is some crumbs and gravy: diversions, corrections and so on that would still be jumping-off points for talks themselves.

Hey, if you don’t want a technical article, what are you even doing here?

Don’ts

Well, there aren’t any don’ts really: it’s your life. But at one point during this project I wasn’t much fun to be around. Being the only engineer on a polyphonic hybrid hardware synthesiser and up against a tight deadline, even if you’re pretty much born for the job, is just a bit too much.

Chris Huggett, industry luminary that he was, never seemed to have this problem when I knew him. He had at least one technical co-pilot within Novation, and usually more than one. For Mininova, it was me and a testing team.

Those were the days (back in 2011) when Chris was still using the processing platform he used throughout most of his Novation career: the Motorola 56000 family. At one point in the early 90s, everybody used this. I call it the Motorola, but they got bought by Freescale, who were bought by NXP, who were bought by Qualcomm … Today, the DSP56F series (as it’s now called) is a forgotten corner of their Galactic Empire and ‘not recommended for new designs’. There are cheaper and easier ways of getting the same horsepower these days. But it was a cool and quirky chip, and he owned the software on it.

The hardware platform

I did the user-facing part of Mininova: MIDI, control surface, menu tree, and parameter management stuff. This was on a separate ARM chip, so the synth engine from my perspective was a big lump of 24-bit memory to which I occasionally poked a parameter or two at Chris’s direction when something salient changed. The other thing I did was make up for a blind-spot of Chris’s which was electromagnetic compatibility [EMC]. Like anybody who has invented their own industry, Chris learned this trade by practice more than formal tuition. He developed his habits in a world where these regulations didn’t yet exist and, by the time they did, he was senior enough to let somebody else look after them.

I missed out the analogue revival part of his story at Novation. Chris moved from the Mininova (his last DSP56F project) to the Bass Station II, which is digitally-controlled analogue, and then the Peak, which apparently has an FPGA to run the oscillators. It seems strange to imagine Chris tackling a complex VHDL or Verilog project in the later part of his career, but that’s what engineers do.

I think I’m fairly safe in asserting that Mantis was the only project that Chris designed with the synth engine running on an ARM. But again, Circuit and Peak came after my time at Novation.

The code

As Chris was a tabs person and I’m a spaces person, I’d reformat his code as I assimilated it, but the changes run deeper than typography. To summarise, while all of Chris’s intentions endure, very little remains of his original code. There are a lot of reasons for this. As I mentioned in the talk, I had other ideas about how to use the chips he’d specified. The Cortex-M4 that runs the sound engine is the most expensive chip in the circuit. We bought it for sound, and it’s a rule of these products that the moment one frees up processor capacity, one finds a new use for it. So it seemed sensible to decouple it from the process of scanning a control surface, which requires mostly donkey-work that a far less capable chip can do instead.

It wasn’t that easy to wrench the synth engine away from the controls in practice. I was doing it against the deadline of Superbooth 2023. That felt like changing the tyres on a car while driving it. I just about made the deadline without breaking what was already there, but at the expense of not having the time to get the new audio converter running properly. The Superbooth prototype made a noise of sorts, but a very peculiar noise that was slightly out of tune owing to Chris’s eccentric choices of sampling frequencies and his habit of hand-baking these choices into derived constants. Paul had to style out my incomplete work during Superbooth and you can see this for yourself. After the new prototype made some really quite interesting sounds, the new chassis was used as a controller for Chris’s original proof-of-concept PCB.

At this point, let us celebrate having a boss who’s been around long enough and listens enough to understand how the development process works in practice. I’ve had managers who would hoik me into an office and call me names for what was effectively the fruit of multiple 80-hour weeks of progress. They were too self-absorbed to acknowledge somebody else’s sacrifice; too ignorant to regard an imperfectly-reached milestone as anything but a miss … Anyway, if I ever took a founder like Paul for granted, I certainly don’t now.

Some of my other changes were for reasons of efficiency: shaving off a few microseconds in places and opening the scope for extra versatility. Some was a result of migrating to a more modern development environment. When I started this project, we took the decision to spend about £1000 on a licence for the same environment that Chris used, which seemed like the cost of continuing his legacy, but it uses a C compiler that dates from about 2010.

New C compilers are magic and older ones are quite dumb. This would optimise by just unrolling every loop it could until I ran out of memory. But drawback of migrating to a more modern, less kludgy version of GCC was breaking changes. I couldn’t take the hacky USB drivers with me because they were sprawling and oddly compiler-specific, and I had to start again. It took a week, post-release, to write a new USB device driver. (You could do a lot worse than the excellent libusb_stm32, because ST’s own documentation for the device takes no prisoners. I rolled my own for the sake of compatibility with my existing protocol-layer stuff, but I found myself getting to know this library very well as a ‘what’ve I done wrong’ crib.)

The rest of the codebase ported in less than an hour, and I went from using all 128 kilobytes of program FLASH to using about 88 kilobytes with no loss of performance.

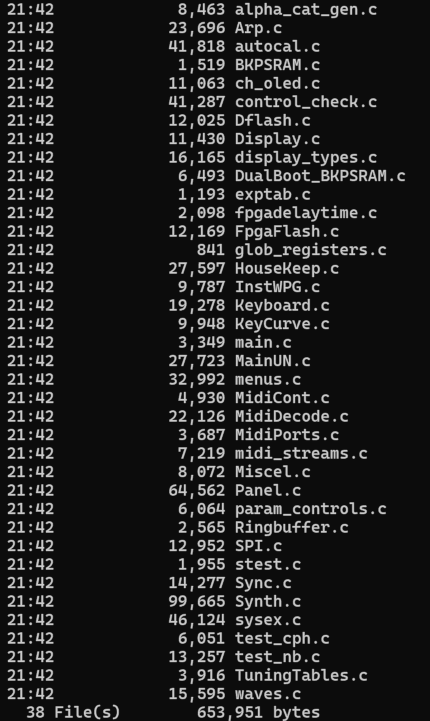

Here are the .c files I inherited:

I shared this source code with a friend who’d volunteered some evenings to help me with the first stages of taking it over: mostly finding which parts of the code were actually part of the project. He’s no small force in this industry, and I guard him jealously. But, after looking through the files for more than a quarter of an hour he asked, ‘Where’s the synth?’

25% of Chris’s code, and most of the salient parts, resided in two files called panel.c and synth.c, the functions of which were nothing like as clearly delineated as their filenames promise.

As you can see, main.c was accompanied by mainUN.c when I took over. Ultranova … There was other third-party code that Chris would have been allowed to re-use, and occasional comments referring to FPGAs in code that didn’t get used betray its pedigree (fpgadelaytime.c, anybody?) It’s a hack of past work that, I assume, would have been cleaned up later had Chris enjoyed better health. (test_cph.c uses Chris’s initials; test_nb.c, I’d assume, is a test routine for an unnamed synth by the inestimable Nick Bookman of Novation. Heaven knows what it was doing here.)

But much of the code was Novation’s: Chris had a licence to use it as a consultant, but we don’t. One reason for a massive refactor was to rebuild our way comprehensively out of any IP issues, while creating our own value in reusable modules. Stubs of code I inherited like menu.c and alpha_cat_gen.c were designed for synthesisers with text handling, imported wholesale for the sake of a few dependencies, so that patch names and other strings sprouted off our screenless synth like phantom limbs. They eventually disappeared without trace.

Refactoring when you’re not precious

Best practices for inheriting code from an absent person or team are well established because it happens all the time. There is a legion of respected books available (search Amazon for ‘legacy code’). But they all assume that you’re inheriting a codebase that has test coverage and that works. It’s bad practice, we all agree, to throw out working, tested code. That’s your company’s competitive advantage. If your code hasn’t yet been deployed, very few rules apply aside from your own taste and judgement.

There were areas where Chesterton’s Fence was actually appropriate: the most careful strategy. Remove nothing until we understand what it does, what its side effects might be, and why it’s written that way. Parse by eye, line by line. Manually eliminate unused variables and branches and check that the thing still compiles and makes a noise. Rename and comment in multiple passes as you go.

A large part of assimilating somebody else’s work is to train yourself to appreciate what’s there. The reverb was exactly like that, and I’ve written reverbs before. It was the only part of the code I printed out and annotated by hand. In hindsight it would have been better to do a first pass through it with my cursor, but I confess I needed a few hours with a pencil and a hard copy.

Some code was compartmentalised carefully so it could be addressed in isolation at my leisure: the usual middle way, and often a precursor to bringing something under unit-test discipline. Chris’s envelope implementation started out as very clear code. Most of my work on it simply modernised the C, clarified the maths, and gave it its own file.

Aside from the control surface, perhaps a third of the code was chuck-away-and-start-again: much of this is because I knew a better way, or already had some hardened library code that would do the same job. The oscillators were rewritten for commercial reasons. I talked at ADC about why I made this decision: we wanted a better palette of timbres and more control than the prototype allowed us.

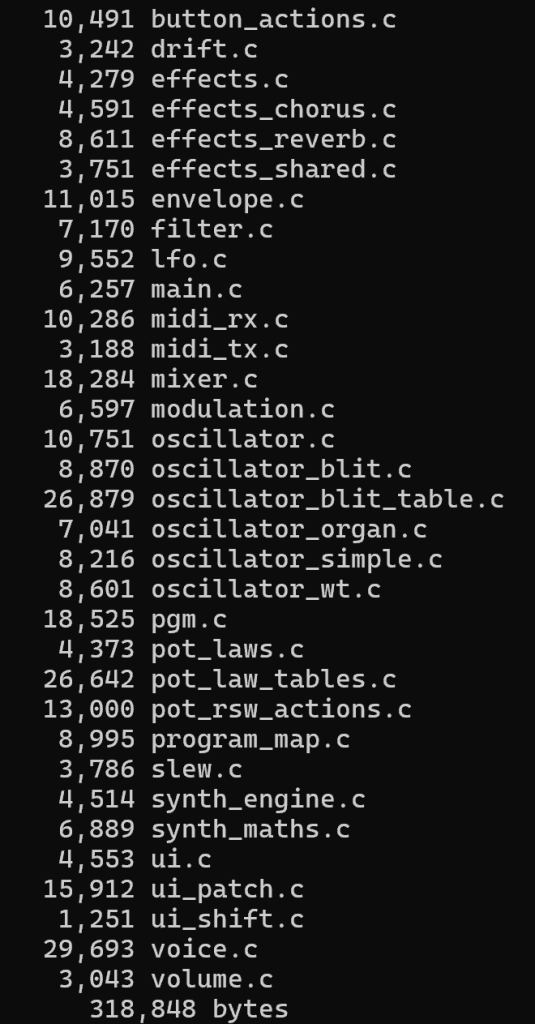

The 99,665 bytes of synth.c became expressed as a number of single-purpose, self-contained, stateless-as-possible source files in a folder called synth/, which is the closest the C language gets to modularity.

The device-specific stuff ended up in a hardware/ folder, and the things I reuse for every project were, as always, in their own included library.

Abstractions are never perfect. Things like the joystick, the FLASH load-levelling for loading and saving synthesiser presets, the obligatory multipurpose buffers, all occupy a liminal space between the hardware and the synth engine. But they’re more properly abstracted than they were.

Incidentally, Chris had decided to generate the wave tables in run-time. This was the only part of his code that used floating point arithmetic (for the sine and cosine operations). I assume he did this either as a temporary measure so he could prototype different waveforms easily, or as a force of habit because the other synths he’d written had very little ROM and ran startup routines that built exactly 100 kilobytes of look-up tables. That used to be a lot. Whatever the reason, I built them ahead of compile-time with a Python script so they could be plucked straight from ROM.

Steal and borrow

The voice management code was the worst part I took over: a mess of side-effectful code that had been imported hurriedly from elsewhere, didn’t properly work, wasn’t the right shape for the synth, and would have taken ages to debug.

Voice assignment remains the biggest, messiest part of this firmware and the hardest to work on because routing notes to voices, and stealing and returning them when you have complicated polyphony rules and two MIDI inputs, an arpeggiator, and local off mode all stealing your attention, is always going to pinch a little.

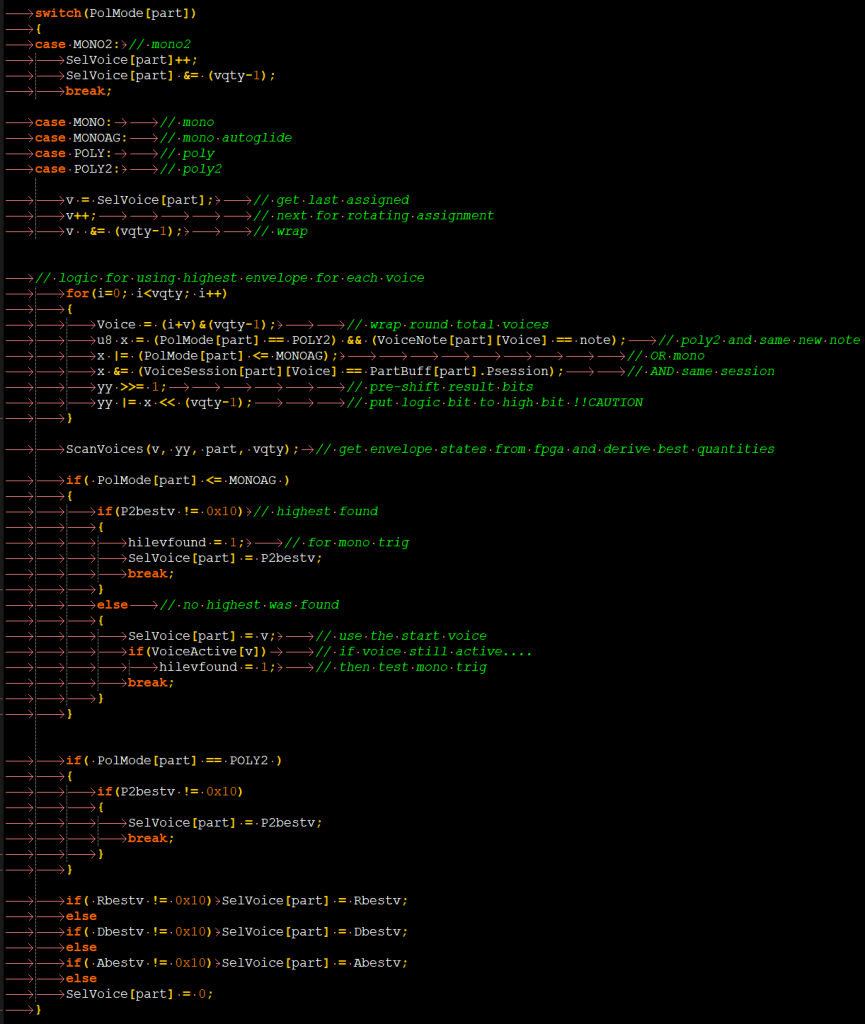

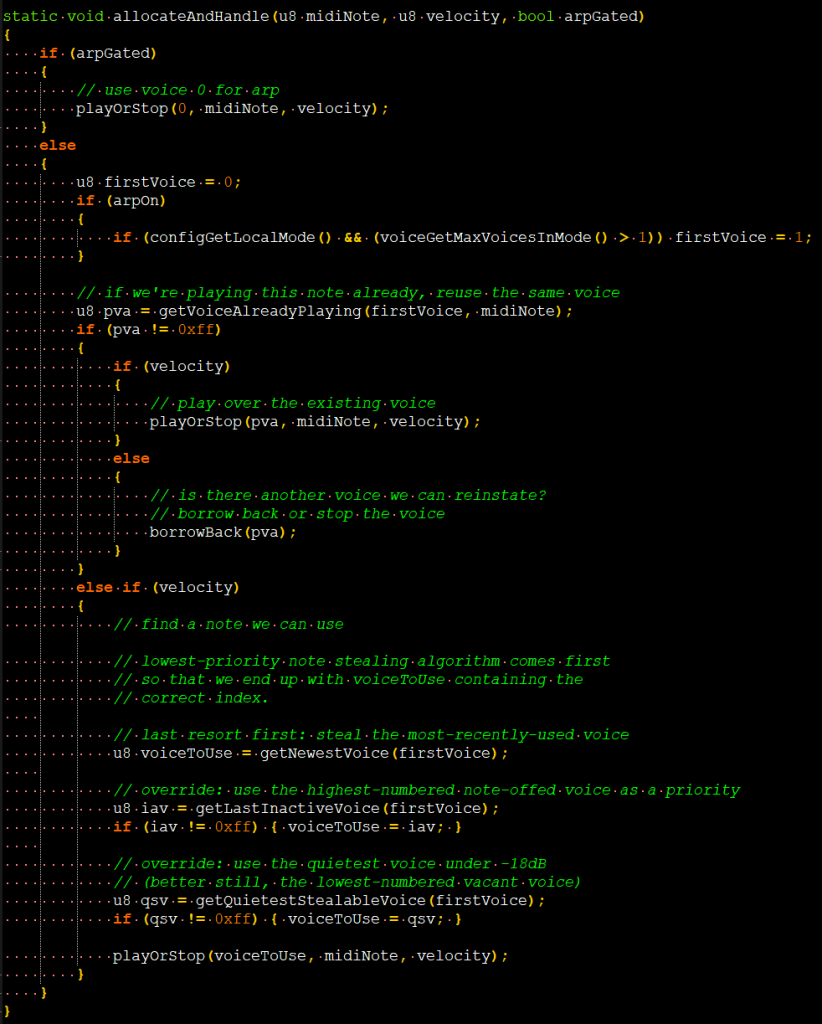

The voice allocator was 300 lines long with 16 state variables and GOTOs: not bad per se, especially given its clear origins in a multitimbral synth, but hard to maintain. Here’s a representative part of it from about 2400 lines into synth.c, complete with loads of state variables and some references to where it’s been used before:

Jules’s first ever keynote, Obsessive Coding Disorder, sprang to mind. My fingers itched to put this right but one approaches code like this with some trepidation: every time you try to tidy it, you’ll add bugs.

During my time at ROLI, I evolved my style about as close as I dared to a C version of the JUCE coding standard because that’s what we followed when we wrote C++. Changes are cosmetic to begin with — that’s the point, they’re for people — but I was able to stop swearing at it and start fixing it once I got the voice allocator to look like this:

I’m still not sure about it: it’d be more efficient written in descending order of priority, but there’s probably a reason why I decided to run every path. This routine gets called only once per note, so there are bigger gains to be had elsewhere.

On a project this size (about 700 kilobytes of source code depending on how it’s counted), you can conduct your own code reviews. Several weeks after writing something, you have no recollection of having written it, no prior assumptions about how it works, and an outsider’s perspective on what you’re like to work with. Good code is written for humans first because a compiler doesn’t spend long enough in the code to care, and these days it’ll blithely optimise away abstractions that aid readability like dividing a long routine into standalone functions so that its structure and intent pops right out of the screen (as above). You get a very stark impression of the limits of your powers.

The voice management code was something I needed two or three good days to tackle. The original work was removed gradually from much of the codebase so it didn’t distract me, which meant that Mantis went from being a duophonic synth in Chris’s prototype to a monosynth until the last three months, when eventually I could face the work. It was not too hard once my fatigue had subsided enough to take it on: the writer’s block came in part from the quality of what I’d inherited. The very final features I made work were the ‘duo’ and ‘quad’ buttons.

Finally, polishing and maintenance aren’t sexy, but they make the difference between a mediocre business and a great one. A potentiometer usually needs a better law than the first guess so the synth responds more musically. Attacks and releases are particularly troublesome because they need meaningful control that spans three or more orders of magnitude of time: 10 milliseconds to 10 seconds, with the same subtlety of control at either end of the scale, is the goal. All this has to be ready before the sound designers can start writing presets, or their work is going to sound different every time they upgrade their firmware.

Fixing bugs can be a two-days-per-week job in the year after shipping but it doesn’t generate money: the advantage it confers is the long-term social capital of reputation. If you’re lucky and careful, many bugs you catch will result in library improvements that fix other projects, and do your future self a favour.

Finesse and fixing is much of the second half of any project. It helps to be a musician yourself because it’s really hard to specify precisely when something feels right.

PS. There’s a glaring bug in the code I flashed up in page 31 of the talk, fortunately with rather minor consequences. No prizes offered for seeing it, but it’s now fixed.

The OSC Advanced Sound Generator

At the end of my talk, I called the ASG prototype that we rediscovered in Chris’s loft the British Fairlight. Although it never saw commercial release, it was demonstrated several times in the mid-80s and there are a couple of published mentions of it that survive online. Here’s a ‘family photo’ of Chris’s early works (with an early Chris). It’s right in the middle of the shot, bulky and glowering with an EDP Gnat balanced on top of it.

The reverse image search doesn’t tell me where this was scanned from so I cannot attribute it. [Update: EDP co-founder Paul Wiffen attributes the picture to Matthew Vosburgh of Keyboard Magazine.] But this picture from my talk, taken by Paul last month, deserves re-posting:

I said during the talk that that this would not be worth resurrecting in anything like its final form. Of course it isn’t. There’d be little hunger in today’s music tech environment for a British answer to Fairlight, even as an app. What’s attractive isn’t the technology or workflow but the principle that gave rise to it. It’s a radical contribution to the ongoing conversation about what a musician’s creative process should look like in five years’ time. You’d have to hit ‘undo’ a few hundred times to create a customer base for 1985’s version of that conversation.

When I propose that the ASG lives on in Chris’s later projects, it’s no mere metaphor. I’d bet that the floppy drive from the front panel ended up in an Akai S1000 prototype. All the more reason for acknowledging the family tree of Chris’s creations that are spiritual successors to the ASG: the Akai samplers; the Supernova digital polysynth and its offspring; the impOSCar software instrument that was very sensitively informed by both OSCar and the ASG.

At some point, it’ll be a leisure project to get that box into a working state, if we can, and to see what vestiges remain of the world’s rarest workstation synth/sampler. I suspect its source code is lost, but Chris did keep some floppy disks from that era, so there’s a fighting chance we’ll find something even if the tools to build it have to be recreated.

If I ever get round to it, of course I’ll be blogging about it.