Now, I work in the synthesiser business because I wanted to be a musician, but also because I wanted to mess with electronics. This thing that I call a career is largely a consequence of being too scared to commit fully to either track, and I’m compelled to try to make a living from what I’d happily do for free. Even so, occasionally I get bored and research things like this.

In the last few months I happened across mentions of a familiar but rather obscure type-in music demo by a composer called Tim Follin, originally published in a British magazine in 1987. I thought this was an ancient curio that only I’d remember vividly from the first time around, with the unprepossessing title Star Tip 2. But apparently it’s been discovered by a younger generation of YouTubers, such as Cadence Hira and Charles Cornell, both of whom went to the trouble of transcribing the thing by ear. (You should probably follow one of those links or you won’t have the faintest grasp of why I’ve bothered to write this post.)

My parents — lucky me! — subscribed me to Your Sinclair at some point in 1986. It was the Sinclair magazine you bought if you wanted to learn how the computer really worked. So I was nine years old when the August ’87 issue flopped onto the doormat. One of the first things I must have done was to type in this program and run it. After all, I had my entire adult trajectory mapped out at that age. Besides, it’s a paltry 1.2 kilobytes of machine code. Even small fingers can enter that in in about an hour and a half, and you wouldn’t normally expect much from such a short program.

When I got to the stage where I dared type RANDOMISE USR 40000, what came out of the little buzzer was a thirty-eight second demo with three channels of audio: a prog rock odyssey with detune effects, crazy virtuosic changes of metre and harmony, even dynamic changes in volume. All from a one-bit loudspeaker. It seemed miraculous then and, judging by the breathless reviews of latter-day YouTubers with no living experience of 8-bit computers, pretty miraculous now. And the person who made all this happen — Tim Follin, a combination of musician and magician, commissioned by an actual magazine to share the intimate secrets of his trade — was fifteen years old at the time. Nauseating.

After three and a half decades immersed in this subject, my mathematics, Z80 assembler, music theory, audio engineering, and synthesis skills are actually up to overthinking a critical teardown of this demo.

The code is, of course, compact. Elegant in its own way, and clearly written by a game programmer who knew the processor, worked to tight time and memory budgets, and prioritised these over any consideration for the poor composer. This immediately threw up a problem of authorship: if Tim wrote the routine, surely he would have invested effort to make his life simpler.

Update: I pontificated about authorship in the original post, but my scholarship lagged my reasoning. I now have an answer to this, along with some implicit explanation of how they worked and an archive of later code, courtesy of Dean Belfield here. Tim and Geoff Follin didn’t work alone, but their workflow was typically crazy for the era.

From a more critical perspective, the code I disassembled isn’t code that I’d have delivered for a project (because I was nine, but you know what I mean.) The pitch counters aren’t accurately maintained. Overtones and noise-like modulation from interactions between the three voices and the envelope generators are most of the haze we’re listening through, and the first reason why the output sounds so crunchy. And keeping it in tune … well, I’ll cover that later.

Computationally, it demands the computer’s full attention. The ZX Spectrum 48K had a one-bit buzzer with no hardware acceleration of any kind. There is far too much going on in this kind of music to underscore a game in play. Music engines like these played title music only, supporting less demanding tasks such as main menus where you’re just waiting for the user to press a key.

The data

In the hope that somebody else suffers from being interested in this stuff, here’s a folder containing all the resources that I put together to take apart the tune and create this post:

Folder of code (disassembly, Python script, output CSV file, MIDI files)

The disassembly

The playback routine is homophonic: it plays three-note block chords that must retrigger all at once. No counterpoint for you! Not that you’d notice this restriction from the first few listens.

Putting it in the 48K Spectrum’s upper memory means it’s contention free. The processor runs it at 3.5MHz without being hamstrung by the part of the video electronics that continually reads screen memory, which made life a lot easier both for Tim and for me.

So there are the note pitches, which appear efficiently in three-byte clusters, and occasionally a special six-byte signal beginning 0xFF to change the timbre. This allows the engine to set:

- A new note duration;

- An attack speed, in which the initial pulse width of 5 microseconds grows to its full extent of 80 microseconds;

- A decay speed, which is invoked immediately after the attack and shortens the pulse width again;

- A final pulse width when the decay should stop.

This arrangement is called an ADS envelope, and it’s used sparingly but very effectively throughout. In practice, notes cannot attack and decay slowly at different speeds in this routine, because it alters the tuning too much.

Multichannel music on a one-bit speaker

The measurement of symmetry of pulse waveforms of this kind is called the duty cycle. For example, a square wave has high and low states of equal length, so a 50% duty cycle.

80 microseconds, the longest pulse width used in Star Tip 2, is a very low duty cycle: it’s less than three audio samples at 44.1kHz, and in the order of 1–2% for the frequencies played here. Low-duty pulse width modulation (PWM) of this kind is the most frequent hack used to give the effect of multiple channels on a ZX Spectrum.

There are many reasons why. Most importantly, it is simple to program, as shown here. You can add extra channels and just ignore existing ones, because the active part of each wave is tiny and seldom interacts with its companions. Better still, you can provide the illusion of the volume changing by exploiting the rise time of the loudspeaker and electronics. In theory, all a one-bit speaker can do is change between two positions, but making the pulse width narrower than about 60 microseconds starts to send the speaker back before it has had time to make a full excursion, so the output for that channel gets quieter.

The compromise is the second reason for the crunchy timbre of this demo: low-duty PWM makes a rather strangulated sound that always seems quite quiet. This is because the wave is mostly overtones, which makes it harmonically rich in an almost unpleasant way. Unpicking parallel octaves by ear is almost impossible.

The alternative to putting up with this timbre is to use voices with a wider pulse width, and just let them overload when they clash: logically ORing all the separate voices together. When you are playing back one channel, you have the whole freedom of the square wave and those higher-duty timbres, which are a lot more musical.

Aside from being computationally more involved, though, as you have to change your accounting system to cater for all the voices at once, you strengthen the usual modulation artifacts of distortion: sum and difference overtones of the notes you are playing.

So, on the 48K Spectrum, you have to choose to perform multichannel music through the washy, nasal timbre of low-duty PWM, or put up with something that sounds like the world’s crummiest distortion pedal. (Unless, like Sony in the late Nineties, you crank up the output sample rate to a couple of megahertz or so, add a fierce amount of signal processing, really exploit the loudspeaker excursion hack so it can play anything you want it to, and call the result Direct Stream Digital. But that’s a different story. A couple of academics helped to kill that system as a high-fidelity medium quite soon afterwards by pointing out its various intractable problems. Still, when it works it works, and Sony gave it a very expensive try.)

There’s one nice little effect that’s a consequence of the way the engine is designed: a solo bass B flat that first appears in bar 22, about 27 seconds in. The three channels play this note in unison, with the outer voices detuned up and down by about a twelfth of a semitone. We’re used to this kind of chorus effect in synth music, but the result is especially gorgeous and unexpected on the Spectrum’s speaker.

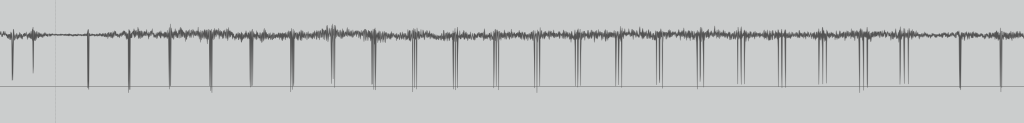

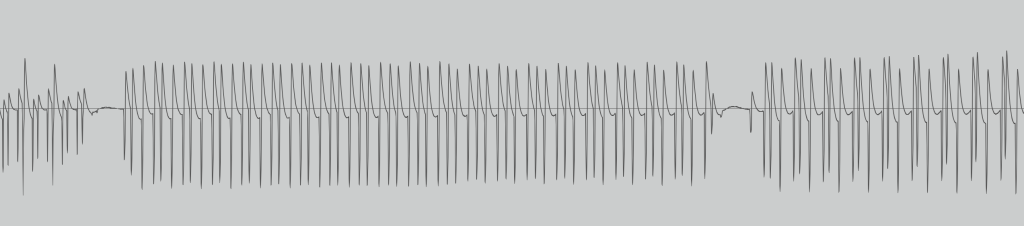

You don’t get many cycles in 0.2 seconds for bass notes, but here’s the three detuned voices in PWM, with the pulse troughs drifting apart over time.

A tiny bit of messing with the code

I didn’t do much with this code on an actual ZX Spectrum, but it’s possible to silence different voices on an emulator by hacking the OUT (254), A instructions to drive a different port instead. You can’t just change them for no-operations or the speed and pitch changes. POKE 40132,255 mutes channel one; 40152,255 mutes channel two; 40172,255 mutes channel three.

Python data-to-MIDI conversion

Are you running notes with a slow attack or decay? If so, the chord loop runs somewhat faster than it does when your code bottoms out in the envelope sustain stage. Are you now playing a higher-pitched note? Your chord loop now runs a little slower on average because the speaker needs to be moved more often, so all your other notes go slightly flatter.

The pitch of every note in this piece of code depends on everything else. Change one detail and it all goes out of tune. I had visions of Tim Follin hand-tuning numbers in an enraging cycle of trial and error, which would somewhat have explained his devices of ostinato and repetition. But it turns out from his archive, now online thanks to Dean Belfield, that he possessed some compositional tools that were jointly maintained by his associates. Having written the calculator in the opposite direction, I can confidently say: rather them than me.

To get the note pitches out accurately, you need a Spectrum emulator, so I wrote the timing part of one in Python. It counts instruction cycles, determines the average frequency of chord loops given the configuration of envelopes and pitches for every set of notes, and uses these to extract pitches and timings directly. The Python data-to-MIDI script takes the data straight from the Spectrum source code, and uses MIDIUtil to convert this to MIDI files.

The code generates three solo tracks for the three voices, follin1.mid to follin3.mid, and all three voices at once, as follin123.mid. The solo voices include fractional pitch bend, to convey the microtonal changes in pitch that are present in the original tune. (By default, the pitch bend is scaled for a synthesiser with a full bend range of 2 semitones, but that can be changed in the source code. Pitch bend is per channel in MIDI, not per note, so that data is absent from the three-voice file.)

The MIDI files also export the ADS envelopes, as timed ramps up and down of MIDI CC7 (Volume) messages. Because the music is homophonic, they are identical for every voice, meaning that the composite track can contain them too.

Microtonal pitch

There are some interesting microtones in the original data. Some of the short notes in the middle voice are almost 30 cents out in places, but not for long, and it seems to work in context. As does the quarter-tone passing note (is it purposeful? Probably not, but it all adds feeling) at bang on 15 seconds.

Cadence Hira’s uncanny transcription is slightly awry in bar 10 here: the circled note is actually a B-half-sharp that bridges between a B and what’s actually a C in the following bar. Meanwhile the bass channel is playing B throughout the bar. But she did this by ear through a haze of nasty PWM and frankly it’s a miraculous piece of work. Two things count against you transcribing this stuff. First, the crunchy timbre issues we’ve already discussed that stem from the way this was programmed. Second, the sheer speed of this piece. Notes last 100ms: your ear gets twenty or thirty cycles of tone and then next! If you’re transcribing by ear you have to resort, as Cadence has, to filling in the gaps with your music theory knowledge of voice leading.

Most of the other notes are within 5 cents of being in tune. Once you expect them, you can just about hear the microtones in any of the multiple recordings of the original (example), but only if you slow them down.

A big CSV file is also generated for the reader’s pleasure, with:

- The time and duration of every note in seconds;

- The envelope settings for each note;

- All the interstitial timing data for the notes in T-states (more for my use than anybody else’s);

- Exact MIDI note pitches as floats, so you can inspect the microtonal part along with the semitones.

Because the detail in the original tune was quite unclear, it wasn’t possible to be sure whether the quirks in tonality were intentional. Originally I did not bother to include microtones, but added them to the MIDI a week after posting the first draft.

I’ve now satisfied my initial hunch that the microtones aren’t deliberate, but a phenomenon of the difficulty of keeping this program in tune. They also happen to be quite pleasant. But going beyond conventional tonality was not essential to appreciating the music, or to recreating the intentions of the composer.

Getting the timing right

Including exact note timings has proved interesting for similar reasons to tonality: the whole notes (semibreves, if you must) are about a sixteenth-note (a semiquaver, if you insist) shorter than intended because of the disparity in loop speeds. That is definitely unintentional because the specified durations are round numbers, with no compensation for different loop speeds. Again, the feeling of a slightly jagged metre works well in context.

But the care I have taken in accountancy seems to have paid off: you can compare this MIDI against an emulated Spectrum and the notes match, end to end, with a total drift of less than ten milliseconds.

The exact reconstruction: mix 1

As a way of avoiding real work, here’s an ‘absolutely everything the data gives us’ reconstruction of Star Tip 2 — microtones, envelopes and all — played through a low-duty pulse wave on a Mantis synth.

In other words, this is simply the original musical demo on a more advanced instrument: one that can count cycles and add channels properly. The only thing that I added to the original is a little stereo width, to help separate the voices.

That B flat unison effect (above) is unfortunately a wholly different phenomenon when you’re generating nice band-limited pulses, mixing by addition, and not resetting phase at the beginning of every note. It’s gone from imitating something like a pulse-width modulation effect (cool) to a moving comb filter (less cool).

The quick and dirty reinterpretation: mix 2

This was actually my first attempt. My original reluctance to do anything much to the tune means I didn’t labour the project, using plain MIDI files with no fancy pitch or articulation data.

But, because I’m sitting next to this Mantis, I put a likely-sounding voice together, bounced out the MIDI tracks, rode the envelope controls by hand, and ignored stuff I’d have redone if I were still a recording musician.

Adding a small amount of drive and chorus to the voice creates this pleasing little fizz of noise-like distortion. It turns out that some of that is desirable.

Epilogue

Now I’ve brought up the subject of effects and production, neither of these examples are finished (or anywhere near) by the production standards of today’s computer game soundtracks. But I’m provoked by questions, and I hope you are too. First, philosophy: could either mix presume to be closer to the composer’s intentions than the original? Then, aesthetics: does either of these examples sound better than the other?

This brings me to the main reservation I had about starting this project in the first place: that using a better instrument might diminish the impact of the work. Star Tip 2 continues to impress because of its poor sound quality, not in spite of it. Much of its power is in its capacity to surprise. It emerged from an unassuming listing, drove the impoverished audio system of the ZX Spectrum 48K to its limit, and was so much better than it needed to be. But the constraints that dictated its limits no longer exist in our world. An ambitious electronic composer/engineer would need to explore in a different direction.

Exploring and pushing technical boundaries, then, is not the only answer. An equally worthy response would be a musical one. Twenty-four years after Liszt wrote Les Jeux D’eaux A La Villa D’este for the piano, Ravel responded with what he’d heard inside it: Jeux d’eau. One great composer played off the other, but the latter piece turned out to be more concisely expressed, more daring, and quickly became a cornerstone of the piano repertoire. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that it influenced everybody who subsequently wrote for the instrument. (Martha Argerich can pretty much play it in her sleep, because she’s terrifying.)

I’m not a composer, though, and definitely not one on this level. A magnificent swing band arrangement of a subsequent Tim Follin masterpiece? Somebody else’s job. Designing the keyboard used in that video? Creating the Mantis synth used above? Wasting a weekend on an overblown contemplation of a cool tune I typed in as a child? Definitely mine.